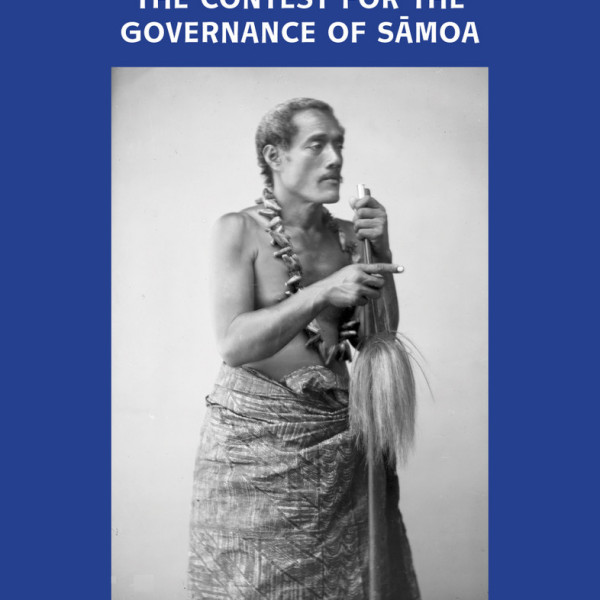

Democracy in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Survival Guide

Written by: Geoffrey Palmer and Gwen Palmer Steeds

Te Herenga Waka University Press

Reviewed by: Kerry Lee

For a lot of people, democracy is the simple process of voting for politicians who you think will have your best interests at heart and will look after you in the short and long term. Unsurprisingly there’s more to it than that, and for those wishing to learn the nitty-gritty of how it works in New Zealand, we have the latest book from Geoffrey Palmer and Gwen Palmer Steeds titled Democracy in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Survival Guide.

Going back to the beginnings of the first Māori wars and the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, it explains how the English style of democracy first implanted itself in our country and how it grew and adapted to serve two very different cultures.

For me one of the best aspects of the book is the inclusion of interviews that the authors carried out. These include ones with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, former opposition leader Judith Collins, and ambassador to Ireland in waiting Trevor Mallard. They give us a rare peak into the mindset of the people that have helped to literally shape our lives in New Zealand. Ardern’s interview in particular stood out for me, as it gave me a better idea of how she thinks and her problem-solving process.

Another plus is the easy-to-read format of the book; I understood everything and never felt like anything went over my head.

One problem is the fact that politics is not for everyone and for some the subject will simply be a turnoff, which is shame because I think we should all have an understanding of the way our country is governed. I would still wholly recommend this book to those people, as it gave even a layperson like myself a better understanding of democracy, and how important it is to remain a part of the democratic process. As it says on the back cover, it’s a survival guide to democracy in Aotearoa.